IPA Vowel Surprise

What I thought I knew isn't what I thought I knew

Getting out my phonetics workbook from grad school has been a fun reminder of learning to transcribe speech in IPA (international phonetic alphabet). I always felt like I was writing in secret code. I loved the fact that every sound had one symbol and I could write exactly what I heard someone produce with their speech, not just the words with regular spelling and not made-up representations of the sounds I heard. I loved the consistency. Lately, I’ve become aware of how differently people learn the vowels in IPA and that it’s not as consistent as I first thought.

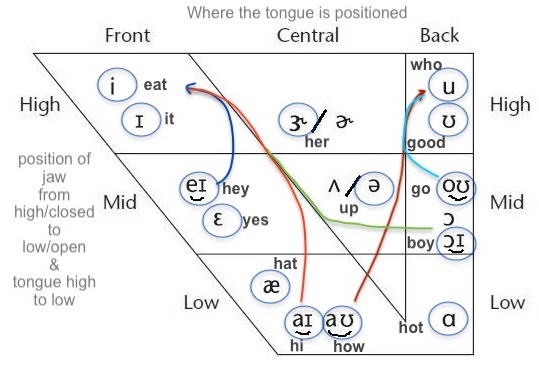

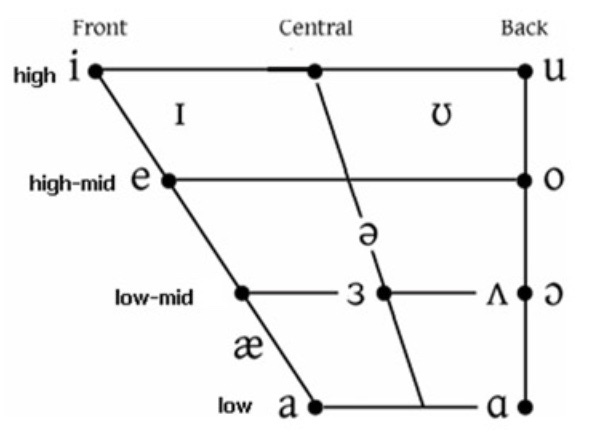

The IPA vowel quadrilateral organizes the vowel sounds based on the height of the tongue and jaw and how far forward or back the tongue is in the mouth. I learned all my vowel sounds in phonetics classes from a diagram marked with these IPA symbols in this organization. Look for the /ʌ/ and /ə/ in the middle.

This /ə/ symbol has a name, the “schwa,” but the /ʌ/ doesn’t have a name as far as I know. I was taught that they are the exact same sound, “uh” like in “up,” just different symbols to represent the vowel with that sound in the stressed syllable as /ʌ/ and the unstressed syllable as /ə/. The unstressed syllable contains a vowel that could be pronounced with its “real” sound or changed/reduced to the schwa sound of “uh.” The stressed syllable contains a vowel that can’t change, it will always sound like “uh.”

So to transcribe the word “above” where both the “a” and “o” sound like “uh,” the “a” can be pronounced as /eɪ/ (sounds like the name of the letter, “a”) but it can also be pronounced as the schwa /ə/ sound “uh.” The “o” can only be pronounced as the “uh” sound, it’s not changing to the “uh” so that’s when I use the /ʌ/ symbol to represent the “uh” in unstressed syllables. I think it looks cool in IPA: /ə’bʌv/.

Something that I had heard from many of my Mandarin-speaking students and clients is that they were taught that the /ʌ/ and /ə/ were different sounds. Well, in my recent researching for updating my materials and writing the book, I’ve come across a lot of vowel diagrams that give a totally different sound to /ʌ/ and it’s what I think my Mandarin-speaking students and clients were telling me they use for that sound.

In this diagram, you can see the /ə/ in the middle and the /ʌ/ way over by the /ɔ/. The /ɔ/ sounds a little like the “a” in “awesome” but with rounded lips. So the /ʌ/ in this position sound more like the “awesome” “a” than the schwa “uh” sound. Listen to compare them on this interactive chart by Paul Meier and Eric Armstrong.

This may seem like a small difference but this has rearranged everything I had based my understanding of English vowels on. This would have been so helpful to know years ago when teaching classes and classes of native Mandarin speaking students who looked at me with confused faces when I used the IPA vowel symbols in a completely different way than they were used to. This small difference has a huge impact on what I had thought was solid ground, it’s not so solid anymore.

I have watched so many people I’ve worked with over the years have “ah-ha!” moments that shook their whole understanding of English pronunciation. This is my “ah-ha!” moment and it’s pretty cool. It has shown me that I got stuck in a rut when I studied phonetics and I should have kept seeking new perspectives and a wider range of information. I will now.

That's funny. Because though it's just me, I always refer to ʌ as "stressed schwa" when describing it. It's funny how speakers of different languages or dialects/accents hear allophones, especially vowels. I'm from America and I got into a rather lengthy conversation with a creator on YouTube just a couple days ago about the U in "Understand". And how in Britain he feels many speakers pronounce it as ʊ. While even when listening to UK tv shows I always here it as ʌ. I still need to go listen carefully to some shows so I can try to hear what he hears.